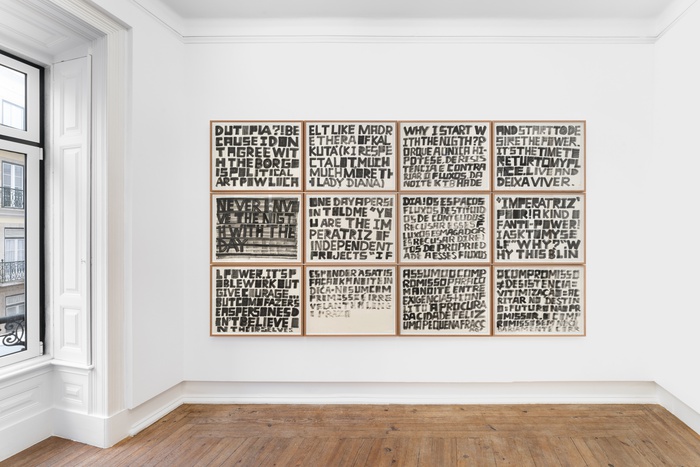

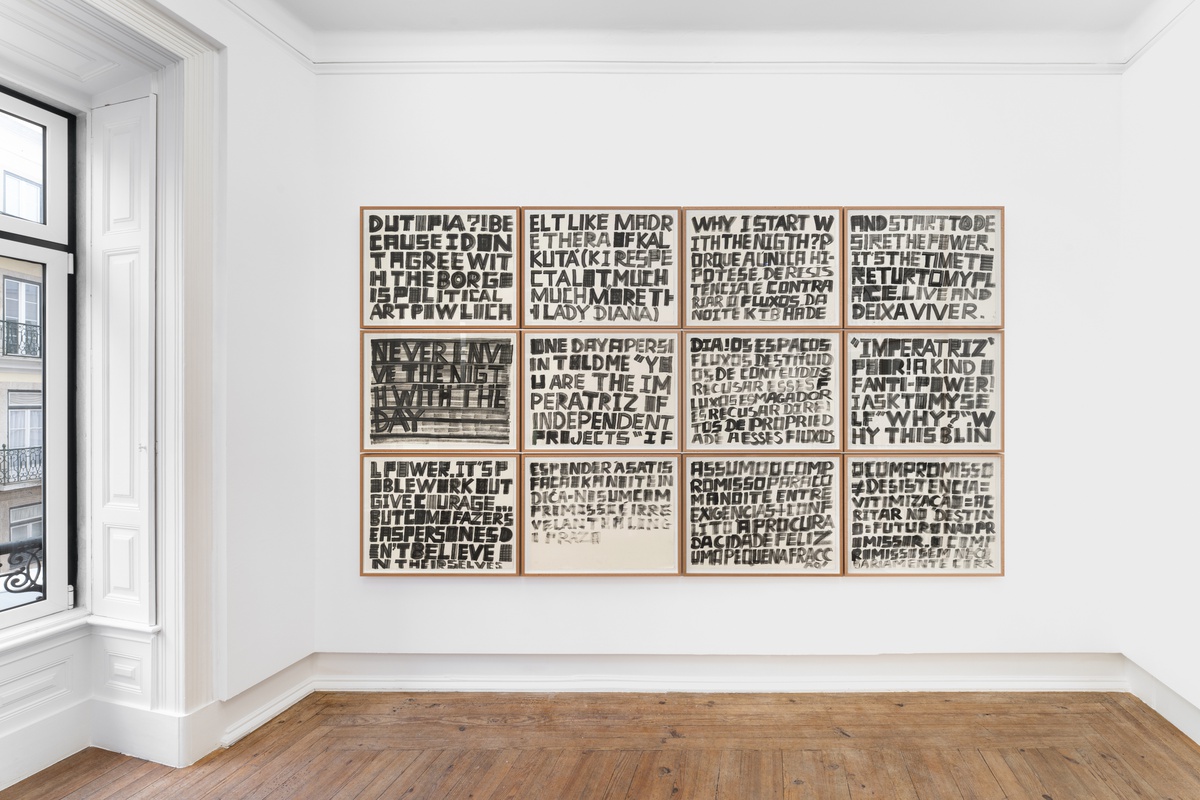

Installation view, Jahn und Jahn Lisboa, 2025

Installation view, Jahn und Jahn Lisboa, 2025

Installation view, Jahn und Jahn Lisboa, 2025

Installation view, Jahn und Jahn Lisboa, 2025

Installation view, Jahn und Jahn Lisboa, 2025

Installation view, Jahn und Jahn Lisboa, 2025

Installation view, Jahn und Jahn Lisboa, 2025

Installation view, Jahn und Jahn Lisboa, 2025

Opening on Thursday, March 20, 2025, 9–11pm

The collector’s house shows no traces of a domestic life, but it is inhabited by the artworks that she has been gathering throughout the years. It is an open space, for socializing, but it is also intimate, even secret. Could we find out what is behind the choice of these works? What do they say of their collector? Could we also find ourselves in the stories they tell and the connections they establish?

In Carla Filipe’s ‘collector’s house’, the first thing to become apparent are the artist’s gestures and experiences as they manifest in her reflections, confessions and questionings inscribed directly on the sets of drawings. Then there is also the presence of the woman body, represented in different historical contexts. In her work there is a ‘tension’ between intimacy and public space, between the individual and the collective (1), which is also symbolized by a collector’s house. Sometimes, this tension is accompanied by a feeling of strangeness, which is not just the result of the political circumstances, social codes and security concerns that restrict urban life, but is mostly focused on the woman body and the historical conditioning and vigilance of its movements in the public space and the obstacles to its mobilization and the creation of ties of solidarity and resistance. Historically, women belong to the enclosed space of the home or the convent, and any deviation from this narrative is bound to be forgotten. Carla Filipe recalls this confinement, but her research, and her independent gesture, also reveal forms and processes of liberation, inter-generational dialogue and rebellion and, finally, the possibility of a community: I speak of the other by speaking of myself. And I speak of myself without stratifying the whole, without evening out the other. When I speak of myself, I allow others to identify themselves and thereby allow for the creation of a community, a plurality. (2)

The process of communing with the other and the ensuing creation of a community are suggested in the works shown in the first room. The experience of urban nightlife establishes a connection through sound and dance, i.e., through the freedom of a more sensorial abandonment. The body’s movements, the vibrations of sound generate foreign bodies that have been brought to the same level by a shared experience and regardless of gender.

This meticulous work of cutting and pasting goes against the art world’s traditional codes of recognition and representation. However, Carla Filipe seeks to find ways of being herself in the art space through an experimental practice inspired in a personal trajectory, which nevertheless always echoes other experiences. It could then be said that the works gathered by the collector form a collective autobiography in which stories of a more private nature also reproduce shared experiences. This collective autobiography tells every-day, trivial stories, thereby encompassing a historical as well as a political dimension. The reference to the dance band FH5, who played international pop music (room 2) in a provincial context for the first time, is an example of a simple story of discovery and contact with other parts of the world. But Carla Filipe’s research transcends such biographic episodes to dive into women’s images and accounts. There is a ransoming of memories not mentioned in history books, which form a non-history or a counter-history. As Ana Sofia Ferreira refers, ‘by 25 April 1974, the feminist struggles of the early twentieth century and their participation in feminist organizations had been erased, either by the regime’s anti-feminist action or because the opposition saw women’s struggle as secondary, something to be diluted in the wider context of democratic claims’. (3)

In the second room, the set of three collages form a memory aid for the control that was exerted over women’s lives and aspirations, as they were rigidly divided into social and professional classes during the dictatorship. While the imposition of celibacy in certain professions ceased, social segregation, represented by the maid’s confinement to the house she served in, continued to exist (and can still be found in the structure of modernist apartments, as well as in new buildings). In this ‘collection’, however, the transgressive stories explored by the artist (such as in My dear and sweet transgressoras, room 2) and their narration through the collage and mixing of images and iconographic subversion, allows for a glimpse between the cracks of official history to re-encounter figures and episodes that complexify women’s experiences, turning them into protagonists and empowering them.

This is clear in her approach to convent sweets and pastries in Alentejo before the Liberal Revolution. Unlike the linear perspective, which repeats traditional victimization, the artist suggests that the women confined to convents (some by their wealthy families) found a space to create, socialize and transgress in the kitchen. These drawings, representing a natural relationship of women to their sexuality, contrast with the collages in which naked bodies cut out from magazines juxtapose conventional erotic gestures and poses and convent architecture to show that the trajectory of women across history was not a progressive emancipation because new forms of control and confinement were constantly being imposed.

In the third room, the visceral manifestations, the entrails bursting out of the body, express that constant strangeness before the more canonical and normalized representation of the woman. On the contrary, the sets of drawings shown here express the possibility of making all bodies visible. As Maria Lamas remarked in a 1975 interview, ‘even the fact of undressing by herself and seeing herself naked is (or was) considered a sin against modesty’ (4). Control in the public sphere was also transferred to the private space, which explains the long silence on women’s sexual desire and pleasure. In these drawings, allergic reactions, the impossibility of hearing or seeing, manifest that refusal of the relentless pressure to follow social norms that push women, their body, their very desires and sexuality into a zone of invisibility. Therefore, the body’s representation as it goes through affective or emotive reactions, or as it is experienced individually, fosters encounter and solidarity: ‘You are sexual remember’, reminds women that motherhood must not prevent sexuality.

Carla Filipe’s work recovers forgotten stories, explores other forms of self-representation and expands the field of representation of women to include the expression of their experiences and intimacy which were rejected throughout history. Therefore, across The collector’s house we discover new meanings for everyday stories and also find ourselves in their constant challenges and possibilities.

(1) Nélio Conceição, ‘The ambivalences of intimacy and aesthetic and political reconfigurations of the common world’, in Rethinking the City: Reconfiguration and Fragmentation, edited by Maria Filomena Molder, Nélio Conceição, Nuno Fonseca, London; New York: Routledge, 2025, pp. 60-76.

(2) Francisco Cardoso Lima and Carla Filipe, ‘Entrevista a Carla Filipe’, in Francisco Cardoso Lima, ‘O Artista pelo Artista na Voz do Próprio’, PhD thesis, University of Aveiro, 2013, Annex D, p. 201.

(3) Ana Sofia Ferreira, ‘O 25 de Abril e as mulheres: uma Revolução incompleta?’, in 25 de Abril: Revolução e Mudança em 50 Anos de Memória, edited by Manuel Loff and Miguel Cardina, Lisbon: Tinta da China, 2024, p. 199.

(4) Maria Lamas interviewed in 1975 by Sílvia Soares in Modas & Bordados magazine, quoted by Isabel Freire, Sexualidades, Media e Revolução dos Cravos, Lisbon: ICS, 2020, p. 232.

Text by Leonor de Oliveira

Bio

Carla Filipe (b. 1973, Vila Nova da Barquinha, Portugal, lives and works in Porto) is a multidisciplinary artist whose work critically examines the intersections of art, politics, and collective memory. She studied Sculpture at the Faculty of Fine Arts of the University of Porto, where she also earned a Master's in Contemporary Artistic Practices. Filipe was a co-founder of the independent art spaces Salão Olímpico (2003–2005) and Projecto Apêndice (2006) in Porto.

Her work has been exhibited at major institutions, including the Serralves Foundation (Porto), MAAT – Museum of Art, Architecture and Technology (Lisbon), Museu Coleção Berardo (Lisbon), MNAC – Museu Nacional de Arte Contemporânea do Chiado (Lisbon), Kunsthalle Lissabon (Lisbon), SESC Pompeia (São Paulo). Internationally, she has participated in the 32nd Bienal de São Paulo (2016), the 13th Istanbul Biennial (2013), the 4th Ural Industrial Biennial of Contemporary Art (Russia, 2017) and Manifesta 8 (Murcia - Cartagena, 2011). Other key exhibitions include La Réplica Infiel at CA2M (Madrid), Les Urbaines at MCBA (Lausanne), and Le lynx ne connaît pas de frontières at Fondation Ricard (Paris).

Filipe has been awarded several grants and residencies, including a Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation grant for a residency at Acme Studios (London, 2009), AIR Antwerpen (Belgium, 2014), the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation Residency (Florida, USA, 2015), Krinzinger Projekte (Vienna, 2017), and Peacock & The Worm (Aberdeen, Scotland, 2023). Her works are part of significant public and private collections, including the Serralves Foundation, MAAT/EDP Foundation, António Cachola Collection, Portuguese State Contemporary Art Collection (CACE), Centro de Arte Oliva, Foundation Leschot; PLMJ Foundation, among others.

Filipe received the FLAD Drawing Award in 2023 and in 2024 the best visual arts exhibition award for In My Own Language I am Independente at the Serralves Museum, by SPA, the Portuguese Society of Authors.

Carla_Filipe_BIO_CV.pdf (1.0 MB)

Carla_Filipe_Press_release_ENG.pdf (1.0 MB)

Carla_Filipe_Press_release_PT.pdf (1.0 MB)