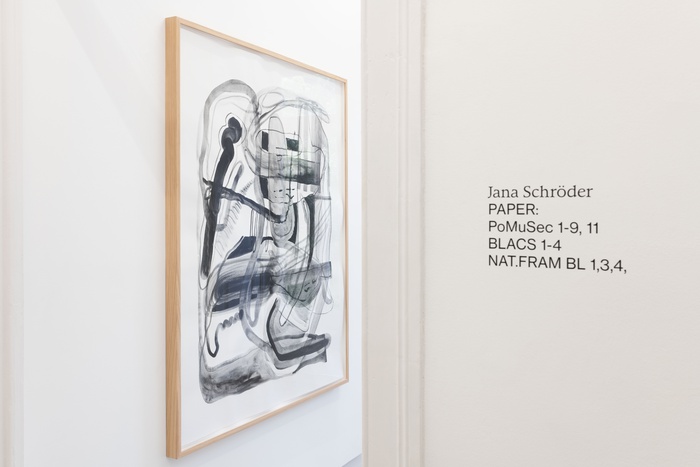

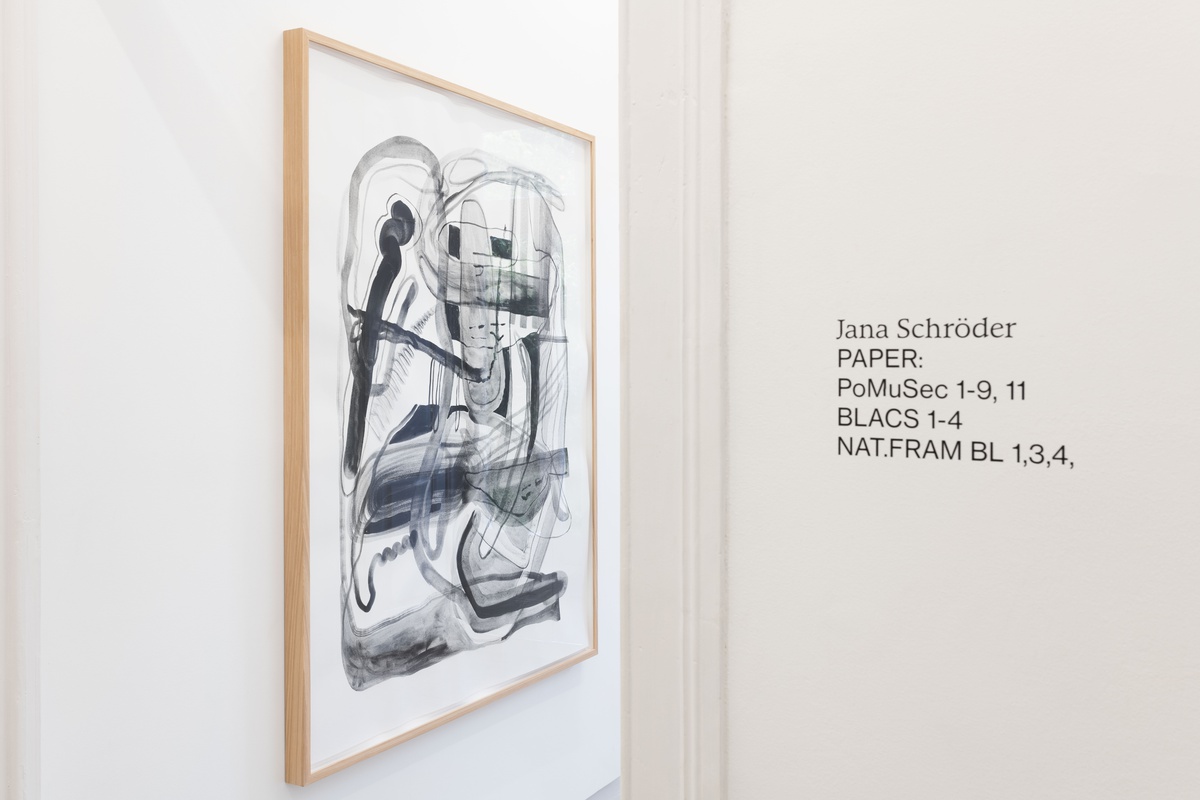

Installationsansicht, Jahn und Jahn, Lissabon 2024

Installationsansicht, Jahn und Jahn, Lissabon 2024

Installationsansicht, Jahn und Jahn, Lissabon 2024

Installationsansicht, Jahn und Jahn, Lissabon 2024

Installationsansicht, Jahn und Jahn, Lissabon 2024

Installationsansicht, Jahn und Jahn, Lissabon 2024

Installationsansicht, Jahn und Jahn, Lissabon 2024

Installationsansicht, Jahn und Jahn, Lissabon 2024

Installationsansicht, Jahn und Jahn, Lissabon 2024

Let us start by directing our thoughts to the moment in which the members of an orchestra come into a hall where soon a concert is expected to begin.

We are comfortably seating in the audience. Around us, spectators look for their places and sit down – some share a few words, greetings are exchanged between acquaintances, shy laughter is heard here and there. Eyes meet, scan the audience, scrutinize the space hesitantly.

And then we hear the cadenced steps of the musicians on the stage and silence begins to fall. We see the members of the orchestra find their places, take their preestablished positions, circle the podium that remains empty at the centre. A crescendo of vibrant strings begins, the wind instruments accentuate different intensities, scales are played, variations experimented, the percussion adjust their drums and manipulate their batons. We experience a feeling of order among the turbulent chaos, an organized disorder, followed by a choreography that becomes tacit as the light intensity in the concert hall diminishes. The musicians are in position, they await a signal. We then see the conductor cross the stage, climb up to the podium and examine the score thoughtfully. The hall is full and now in the dark; only the stage is illuminated. Silence becomes palpable, it permeates the space. Expectation becomes tangible. The conductor’s deliberate gesture gives the order and, almost imperceptibly, we hold our breath. Something extraordinary is about to take place.

Entirely concentrated on what unfolds, we let ourselves be spontaneously transported to another space, another time. A place of a non-objective order. As Walter Benjamin remarked, a phenomenon of distraction occurs in the contemplative order, we are deeply distracted precisely because we have become ‘self-forgetful’ (1). And this self-forgetfulness takes place as we experience the delicacy and brutality, the proximity and the distance, the unsettlement and the violence, the familiarity and the strangeness in the opening up of the vast field of possibility that is laid before us in the confrontation with the work of art, in which time and space acquire a new dimension. As José Gil writes, ‘the work of art produces a space and secretes a time of its own, which are neither subjective nor objective. These are engendered by the image-forming process itself. (...) An image’s space-time is the element-medium that constitutes its very substance’ (2).

The work of Jana Schröder unfolds precisely on this horizon. Like a conductor’s gestures leading an orchestra, the artist’s gesture occurs through the cadences of her moving hand and thought. By applying more speed and fluidity, more slowness and resistance, Jana Schröder creates a universe of images that challenge signs and referents. The gesture is imperative, spontaneous, it does not seek an end. The image is built of lines and stains which can be denser or more transparent, of velocity and restraint, pauses and repetitions, lightness and weight. The verticality of these forms, meandering or broken, transports us to a vertiginous, kaleidoscopic universe where disorder is only apparent, because the addition, juxtaposition, conjugation, constant weaving of the intricate webs of forms that create different moments, different rhythms, different scales, generate an ordered chaos that governs their totality. It is an ode to movement, to the free gesture intrinsically connected to the gesture of thought, as José Gil claims: ‘It is the form of gesture that embodies, unfolds and reveals thought. The unfolding of gesture reaches its target almost instantaneously as instantaneous becoming of forms. (...) movement must be free and rely only on itself’ (3).

This truly free gesture in Jana Schröder’s work allows us to know and understand the abstract time-space which the work of art inhabits. Our expectant and attentive gaze, intensely absorbed via our concentration-ability, recognizes itself as a constructive element of that other place in which the work occurs: it examines the work’s forms, its surfaces, its distances and nearness, its intensities and rhythms. We stand in another place, experience another time. Like in the concert hall, as the conductor’s gesture sets things in motion. The orchestra charges and we, the spectators, lean back in our seats, holding our breath for an instant, abandoning ourselves to the power and energy of creation. As Paul Klee wrote: ‘Didn’t Feuerbach say: For the understanding of a picture, a chair is needed? Why a chair? To prevent the legs, as they tire, from interfering with the mind’ (4).

Filipa Correia de Sousa

(1) Walter Benjamin, in ‘The Storyteller’, available at https://arl.human.cornell.edu/linked%20docs/Walter%20Benjamin%20Storyteller.pdf [accessed 2 April 2024], p.5.

(2) José Gil, A Imagem Nua e as Pequenas Percepções. Estética e Metafenomenologia, Relógio D’Água Editores, Lisbon, 2nd ed., 2005, p. 179. [Our translation]

(3) Ibidem, p. 192. [Our translation]

(4) Paul Klee, in The Thinking Eye: The Notebooks of Paul Klee, Jürg Spiller ed., University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, 1961, p.78.